On Saturday, November 12, 2022, a B-17 and Bell P-63 Kingcobra collided in mid-air at a Dallas airshow. The accident resulted in the loss of all six people on the two aircraft. The topic of Airshows first appeared in the Flight Test Safety Fact (FTSF) in Issue 19-04, and it generated a lot of discussion and feedback. But the timing of this incident is important for several reasons. First, the late Des Barker (SETP), diligently documented airshow mishaps for several years in the Cockpit magazine and in presentations at various symposia, as he did here. I believe the work ought to continue and wonder who will pick up the baton and what we can do to ensure the preservation and publication of this important information on a yearly basis. His article supplements resources on the FTSC website, like the Airshow/Flight Demo guidance document on the Recommended Practices page. Second, as I considered the accident and discussed it with members of my family, I also wondered, “Is it worth the risk?” The question is something we all ought to answer again.

As I pondered, I considered wild ideas like airshows with remotely piloted B-17s, and I quickly recalled another B-17 mishap from August 25, 1952. In the 1950s, a manned USAF B-17 from Duke Field, Florida, was inadvertently shot down over the Gulf of Mexico. The aircraft—piloted by members of the 3205th Drone Group—was the airborne control platform from which a crew member operated the target, a second, remotely piloted B-17. The fighter pilot conducting the live fire misidentified his target. Drones have been with us since the beginning of aviation, and in particular, subscale flight test of unmanned aircraft predates the first powered flight. Flight Test has been telling these stories since 1977, when SFTE’s masthead, the Flight Test News, reported that Remotely Piloted Vehicle System Completes First Automatic Flights.

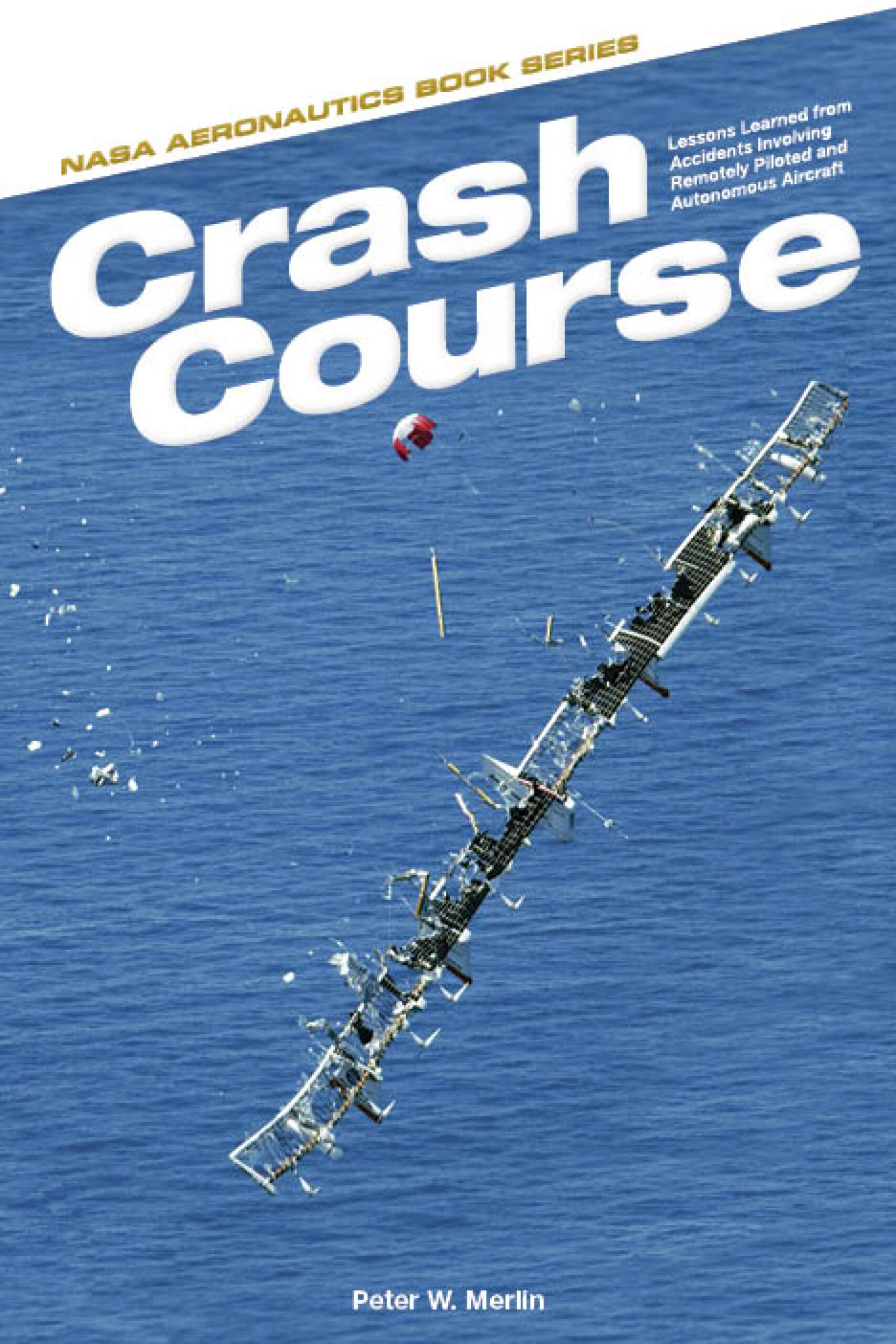

Recently, however, DARPA and Lockheed Martin partnered for a full-scale flight test demonstration of an unmanned Blackhawk helicopter. I believe the state of technology readiness suggests two things: 1) flight test of drones will continue and even increase; 2) whether you call them remote pilots or operators, humans are the most important feature of this testing that will reduce risk and increase safety. To support this claim, I recommend Crash Course, a monograph published by NASA’s Peter Martin. (Download the pdf at https://www.nasa.gov/connect/ebooks/crash_course_detail.html.)

The 2013 book opens with the 1970s era history of the F-15 Remotely Piloted Research Vehicle, a subcale drone used to collect high-fidelity data to inform the spin test program conducted by McDonnell Douglas and the U.S. Air Force. I recommend the book for this audience, both for the historical context and its relevance to modern technology. In the first chapter, I encountered the name Einar Enevoldodson, a name that the younger generation of flight test safety professionals probably has little cause to remember. Einar was the first remote pilot of the F-15 RPRV. His observations about remote piloting and the objective data gathered about his physiological response to the task are both astounding.

NASA photo: F-15 RPRV cockpit

Since the title of the monograph is Crash Course, you can probably guess (as I could) what happens at the end of this story, but I found the ending surprising for three reasons. First, it was the test systems that failed and caused the mishap. The recovery chute system proved troublesome for much of the program. I don’t know if we are as diligent about test safety planning after we put all the mitigations in place, looking at risks added to the program by test systems. Second, the remote pilots actually intervened and prevented mishaps in some cases. After failures of multiple systems and a failed recovery attempt, a pilot noticed the uplink to the aircraft had been restored. The pilot took over and flew the aircraft to a forced landing on the lakebed at Edwards, thus preventing a crash. Third and finally, the “findings” and determination of “root cause” seems overly simplistic and unhelpful in many cases.

I wish I could do justice to this third, incompletely articulated statement, but you will have to read the words of Dan “Animal” Javorsekt in FTSF 20-08 to get the full sense of what I mean. Here’s an excerpt:

Dan “Animal” Javorsek has something to say about determining root cause. In particular, he believes that we tend to make overly-simplistic conclusions in post-mishap reviews and accident investigations, as he states in his own words below.

“…when viewed in reverse, the event appears straightforward to predict. To best demonstrate this…it is convenient to consider a single particle of pollen floating in a glass of still water. After several hours of random collisions with adjacent water molecules, the pollen will have traveled about an inch under normal conditions.”

If Brownian Motion and root cause pique your interest…well, I hope they do and you read the full article.

There is one other topic I won’t be able to address completely in this column, Emergence. Can anyone ever fully address the topic? It’s been discussed at length again this season of Symposia. I recommend an early essay on the topic: The Tacit Dimension by Michael Polanyi. I found a host of applications to flight test safety.

I think you will find a lot of topics that I barely addressed in this edition, but I prefer to think of them as sparks…maybe something in your mind and heart will catch fire. If so, send us a note and tell us what you think.

Related: Flight Test Safety Fact, 22-12