This article first appeared in the January 1971 Flight Test News.

CALVERTON, N. Y., DEC. 30, 1970.

No. 1 F-14 crashed and burned in a wooded area about one mile south of the runway here this morning returning from its second test flight. Both pilots on the flight, Bill Miller and Bob Smyth, ejected safely from the aircraft and are in fine condition. There were no people injured on the ground, nor was there any property damage on the ground.

The flight had started at 10:08 a.m. Accompanied by three chase planes, the F-14 lifted off from the Calverton runway, climbed effortlessly into a dazzling blue sky, banked right, and turned southeast toward the flight test area over the Atlantic Ocean. On the ground, about 50 people, including Company officers and program and flight test personnel, watched the twin-jet fighter as it disappeared over the horizon.

For the first 20 minutes or so, Miller, who was piloting the plane, and Smyth, Grumman Chief Test Pilot who was monitoring instrumentation equipment, flew the F-14 with wheels down, while testing the craft’s stability and control in various flight maneuvers. Then they retracted the gear and accelerated slowly from 133 knots to 180.

The first hint of possible trouble came about 25 minutes into the flight. It was then that Bill Miller reported a loss of pressure in a prime hydraulic system (a chase plane also reported fluid streaming from the craft) and that they were returning to Calverton. At the time of the initial failure, the F-14 was about 30 miles southeast of the field, about 4-5 miles over the water, flying at 14,000 feet.

Back-up system

The F-14 has two prime hydraulic systems working in tandem-if one fails the other automatically takes over the entire workload in actuating controls, etc., necessary for operating the plane in flight.

Although there was evident concern among those awaiting the returning plane, everything seemed under control in the air, with both Miller and Smyth reporting progress of the flight in unhurried, precise terms.

Miller delayed lowering his landing gear until the plane had descended to about 2,500 feet and was about four miles out and in sight of the runway. When he announced over the radio that he had blown the gear down with pneumatic pressure – “Nose wheel down and locked, both main landing gears down and locked” – there was a concerted shout of relief from the ground.

That mood changed quickly. Just a few minutes from touchdown, Miller re- ported that the aircraft had lost its flight control system (the other prime hydraulic system) and in a desperate effort to save the test plane, Miller switched to the Combat Survival System that allowed him to operate certain flight controls. (Normally, this option is used only at higher altitudes to permit a pilot to fly away from a trouble spot, say an enemy combat zone, to a safer area where he might eject.)

‘Can’t hold it’

But it was too late. The F-14, only a few hundred feet above the trees in its final approach to the runway, dipped lower and lower. Miller was fighting to hold the plane in the air but it began to porpoise, nose up, nose down. Finally, Miller informed Smyth, “Nope, I can’t hold it-eject!’ It was 10:45.

As flight crews, Company officers, and various members of the F-14 team watched, the F-14 disappeared into the trees, exploded, and sent a giant fireball rising into the morning sky. Disbelief turned to grief.

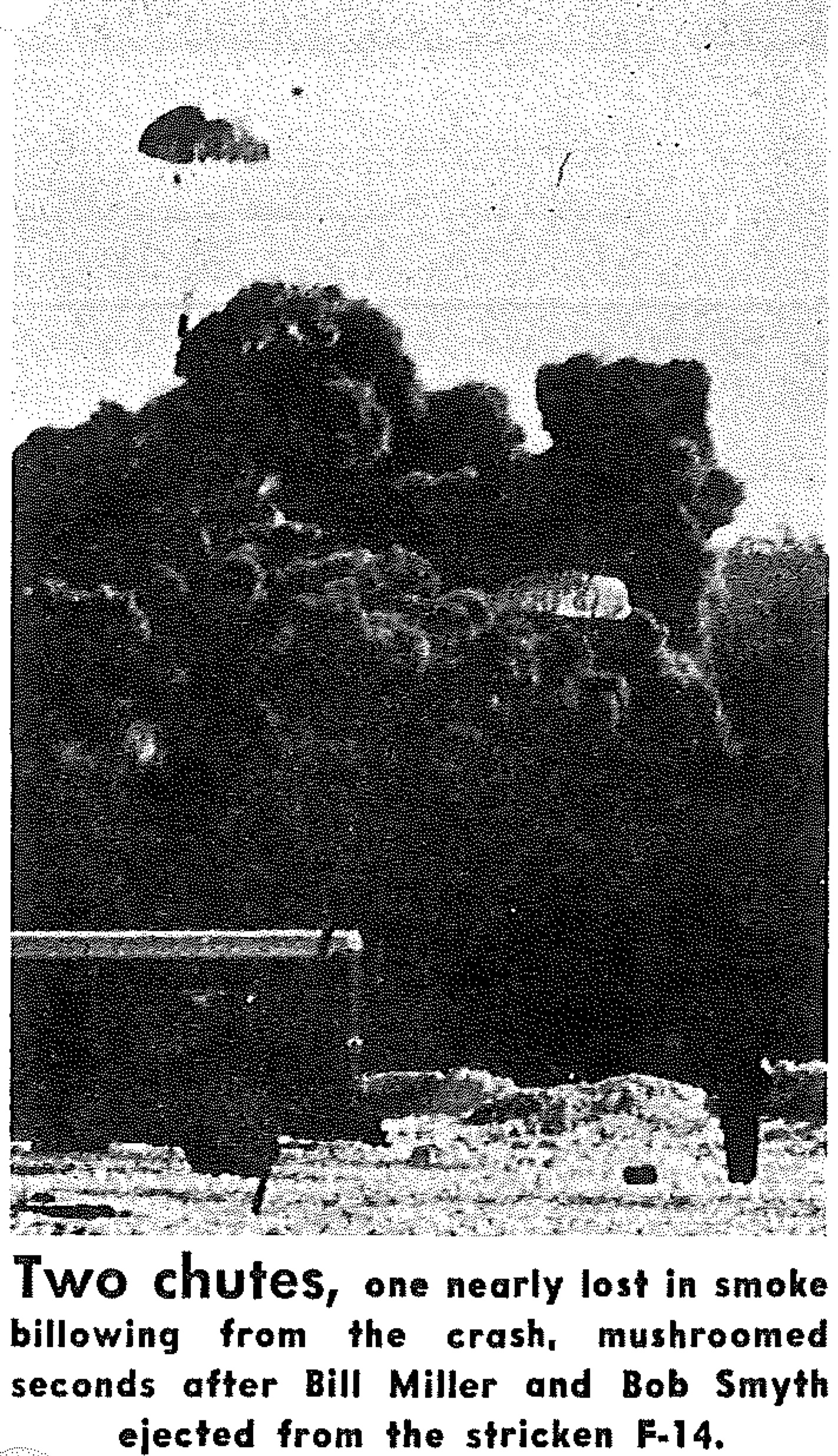

Through the black smoke, however, first one, then two mushrooming para- chutes were spotted from the field but the feat persisted: Was it possible for two men to eject practically at tree-top level, in close proximity to the crash site, and survive?

When the rescue team reported some minutes later that both pilots were safe and unharmed, there was a loud cheer of unrestrained relief. Bitter disappointment had been sweetened by the safe return of Bill Miller and Bob Smyth.

In a debriefing session shortly after their return to the test flight facility here, Miller and Smyth described their flight at some length. The only apparent evidence of their narrow escape was a small Band-Aid on Miller’s hand.

One veteran pilot who was on the scene during the entire event noted that “I’ve never seen guys so cool after such a harrowing experience.” And his estimation seemed to hit the mark. Smyth, who piloted the F-14 on its maiden flight December 21, remarked that “I just sat obediently” until Miller decided they had to eject.

Smyth’s troubles weren’t completely over. He started to come down into the fireball, but “the thermal action from the fire carried me up and away to a safe distance-but my chute got singed.” Miller’s only concern, reports a crash-rescue man who met him walking away from the crash scene, was for Smyth’s safety. He hadn’t seen Smyth’s parachute mushroom and was worried about his flight mate.

Ejection system successful

Both were saved by the F-14 seat ejection system. The seat-ejection system had been proved out successfully earlier this month at China Lake Naval Weapons Center by an F-14 Crew Escape and Ejection Systems test team. Using instrumented dummies in an F-14 cockpit mockup mounted on a rocket-propelled sled, they chalked up a whole series of ejection conditions, from zero altitude/zero velocity to 600 knots.

The system, first demonstrated at Calverton in August, is the first that Grumman has used with a canopy lock severance system, and the first with zero-zero capability. The canopy and Martin-Baker seats are ejected, in sequence, so as not to collide; an underseat rocket gives additional boost, and a parachute system slows the fall to earth.

A full report on the F-14 accident will not be officially released until the Navy convenes its accident board which will investigate and try to determine the exact cause of the crash.

Some results significant to the F-14 Program reported after the flight were:

- The No. 2 F-14, scheduled for completion early next year, is instrumented to obtain low-speed technical data that will be needed to meet program requirements. The loss should not unduly delay the program although some changes to instrumentation may be required to collect the data which would have been developed by No. 1 F-14.

- The general handling characteristics were checked to confirm that the de- sign substantially meets its overall qualitative requirements.

- The failure that induced the difficulty was not in the primary structure or propulsion system.

- A re-evaluation of auxiliary systems will set new safety standards and criteria applicable to the whole F-14 series and possibly for other aircraft as well.

- Since the F-14 Program is ahead of schedule, it is expected that any program delays will be minimal.

Following the accident, President Lew Evans said: “We’ve got a great airplane here, and although we’ve had a setback today, as far as I’m concerned, nothing will slow the program.”

This article first appeared in the January 1971 Flight Test News.

One thought on “Miller, Smyth safe after F-14 crashes returning from test flight”

Comments are closed.