by Bill Jaconetti

This article first appeared in the May 2015 Flight Test News.

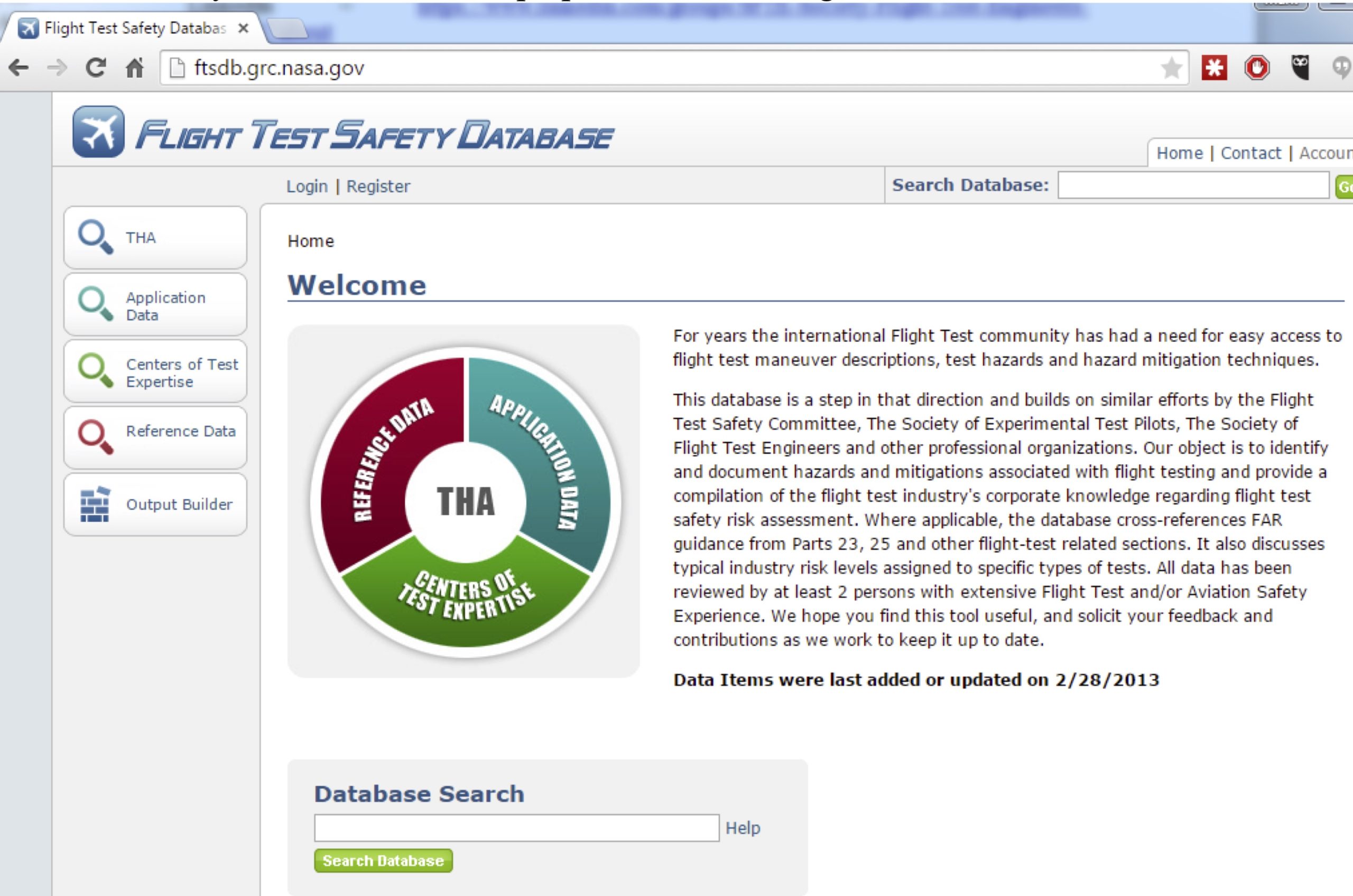

Better THAs

One of the resources available to all members of the aerospace community is the Flight Test Safety Database, as seen above. NASA hosts this website, a project sponsored by the FTSC. The database provides a search function for test hazard analyses (THAs) with a variety of useful filters. The test community would benefit greatly if users “played with” the database, learned its features, and populated it with improvements and new THAs. John Hed and Ralph Mohr are two current members of the FTSC Board of Directors with whom FTN spoke in preparation for this edition, and they could not say enough by way of encouragement to SFTE members, about the database. In addition, SFTE Board of Directors member Bill Jaconetti is currently the chair of the SFTE Safety Committee and has prepared the following observations on THAs.

Test Hazard Analyses

A critical part in the planning process for any flight test is the Test Hazard Analysis (THA). If you are part of a military program, work at a major aircraft manufacturer, or have just been around flight test for a while, chances are you have a process in place to help guide THA development. This article is not meant to replace procedures your group may have, but to illustrate some best practices and relay the frame of mind I get into when doing a THA.

Hazards and Risks. To best understand how to develop an effective THA, we need to first talk briefly about hazards and risks. A hazard is a present condition that could contribute to an undesired event, such as an accident. Risk is the future impact of a hazard that is not controlled or eliminated. It can be thought of as the future uncertainty created by a hazard. In general, risk can be expressed as follows.

Risk = (Hazard) x (Exposure to the Hazard)

Identifying Hazards. The hazards need to be identified and analyzed to develop a risk profile for an individual test. This step deserves much of our focus and concentration. In the wake of the Apollo 1 disaster, NASA suggested this:

“What we really learned from the Apollo fire, in the words of [former astronaut] Frank Borman, was the failure of imagination,” said William H. Gerstenmaier, NASA’s associate administrator for space operations. “We couldn’t imagine a simple test on the pad being that catastrophic.

“The failure of imagination.” What a powerful phrase! What it means is that the complexity of aircraft design, the proliferation of software based systems, etc.—all of these things create hazards that we haven’t even begun to imagine.

There are three main steps I use when identifying the list of hazards that go into a THA:

- The bottoms up review of the test plan

- Focus on the plan, the system under test, the environment, and other unique factors that may present hazards in the test.

- Some hazards are the result of aircraft (im)maturity, and some are the result of exposure, i.e., danger inherent in a maneuver. (The former hazards may not present as much risk as the latter after development testing is complete).

- Other Resources

- Your experience

- The experience of your teammates and/or organization (similar tests on other projects/programs)

- Industry Guidance (FAA Order 4040.26, US Navy/US Air Force Equivalent)

- Other industry specialists

- THA databases (NASA/Flight Test Safety)

- Brainstorming

- Step back and think: what else can happen that is unique to this test?

All three of the steps are important in developing a comprehensive list of hazards. Using only what was done in the past, just like ignoring past plans can leave you with an incomplete list. Finally, a hazard should have a consequence associated with it. The consequence is what will happen to the system under test and/or crew if the hazard occurs.

Turning Hazards into Risks

Once hazards are identified and analyzed, the next step is to generate the risk level for the hazard. Per the definition above, to establish the risk level, the exposure to the hazard has to be quantified. For example, your exposure to a loss of control hazard may be significantly lower for a test that integrates a new display than it would be if your plan contains stall testing. Further, THAs should not include hazards that are part of normal flying. All THAs should be specific to the testing involved. For example, even though bird strike can always be a problem, a function and reliability test might not need a risk for bird strike. However, if you are doing low altitude flight testing for a Ground Proximity Warning System it may be appropriate to have a hazard for bird strike since the test drove specific exposure to the a hazard that was above and beyond normal flying.

The combination of the likelihood and the consequence can help you to assign a risk level. There are many published examples of likelihood vs. consequence tables that are available for translating hazards into risks, but most have high/high resulting in High Risk, and low/low at Low Risk with a standard distribution in between.

Mitigating Risks

When the risk levels are understood and assigned, it is time to mitigate each risk. In some cases the risk from a hazard may still be high, but the key is that it was brought to an acceptable level of risk. You can think about total risk as being a combination of the Identified and Unidentified risks (see graphic below). Of those identified, there are acceptable and unacceptable risks. We don’t test with unacceptable risks. The combination of the acceptable risks and the unknown risks, defined as the residual risk, is what we accept when we go test. All of the steps listed above can help to drive that area of unknown/unidentified risks to be as small as possible.

The mitigation steps for each risk can come from many places. Mitigation may be based on analysis or reports from other engineering disciplines, ground testing, specific training or a multitude of other risk management processes. Be as specific as possible to your application and avoid the temptation to just re-write the standard mitigation you may have used before. Also, the mitigation steps will likely be read many, many times throughout your program, so be as succinct as possible. This is not the time to be wordy!

Organizing the THA

Regardless of whether your THA is resident in your test plan or in some separate document or database, it is critical to tie a THA to a specific type of test. Additionally, each organization should maintain a master list of THAs to ensure consistency between test plans with similar hazards. There may be some hazards that are general to the program, and those will be tied to any flight, but most will be test specific. By creating a coherent link between a THA and a type of testing you can ensure that when planning an individual test, you capture all the THAs needed and none of the ones that are not applicable.

As a final thought it is easy to get caught up in the THA and risk management process, but we always have to remember that our job in the end is to test these systems. There will be risk, but in the balance between test efficiency and safety, it is the test team that identifies and manages risk most effectively that will ultimately be the most successful.

This article first appeared in the May 2015 Flight Test News.